Exploring the L. Hollingsworth Wood papers

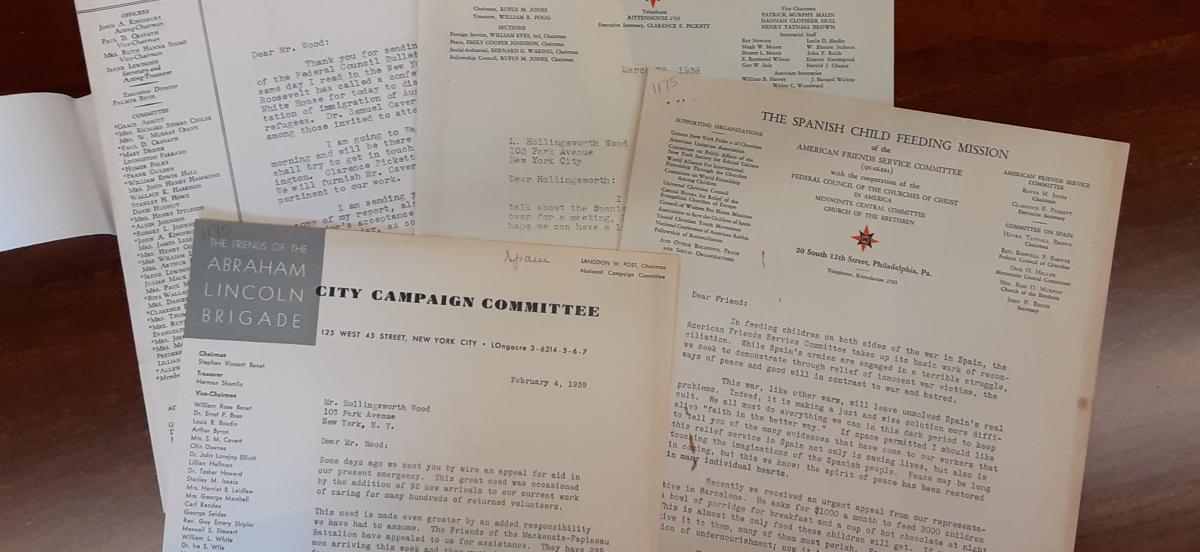

Correspondence from Wood's work with the Spanish Child Welfare Association, which sent food aid to Spain during the Spanish Civil War. This is one of the many philanthropic groups Wood was involved with.

Details

Ella Culton '23 describes what she has found while working with the papers of Quaker philanthropist L. Hollingsworth Wood.

The L. Hollingsworth Wood collection is a massive undertaking- 81 boxes worth of materials, with many folders filled to the brim. It has been my job this summer to sort through these materials, organizing them so they are easily accessible, take up less space on the shelf, and ultimately, update an online collection guide for patrons. While the collection is named after L. Hollingsworth Wood, and you might assume then that it is all about this Haverford graduate, it in fact has very little to do with him. Wood plays tangential roles in many of the organizations featured in his collection, often a member of the executive board, or involved in finances. Arguably the most important materials in his collection are related to civil rights, including his work on health and services for African Americans in cities. The National Urban League and New York Colored Mission, two organizations Wood was a member of, devoted significant time and energy into “improving conditions” for African Americans, often focusing on women and children through support services and education programs.

But underlying the success of these critical social services was a problematic power dynamic which influenced every aspect of the work- it is impossible to ignore that Wood, and most of his colleagues, were white and wealthy. A promotional fundraising card for the New York Colored Mission reads as follows: “Will you help the Colored People here in New York City? There are about 80,000 of them. Many are still slaves to ignorance, laziness and vice. We are trying to free them…”. Rather than individuals who held their own inherent value and talents, African Americans in New York, in the view of the New York Colored Mission, were dented objects that needed just a *little* retouching and polishing before they could be productive workers and members of society. This white savior narrative appears throughout the collection in the philanthropic work of Wood.

What seems to complicate this picture is that the National Urban League and New York Colored Mission did, in many cases, genuinely good work. Both organizations believed in the restorative powers of fresh air for the mind and body, and as a result, created programs to get women and children out of the city, into the country or seaside, free of charge. This is especially beneficial when you consider the tuberculosis epidemic of the 1900s in the context of racial healthcare disparities.

While I haven’t quite reached the end of the L. Hollingsworth Wood collection (less than 10 boxes to go), I’d argue I have a pretty complete picture of the materials. Wood brushed shoulders with many important figures of his time like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, just to name a few. He could proudly say his philanthropic work made a difference. But most of all, what I come away with from his collection is not awe about Wood and his achievements, but curiosity about the many unnamed or brushed over people of color that the collection references. The Wood collection spans from the late 1800s through the 1950s, and I highly recommend diving into this tumultuous and incredibly important period in US and Quaker history.

-- Ella Culton '23