Hidden Collections - A Recap

Quaker cookbooks

Details

This month marks the sixth month of Quaker & Special Collections Project cataloger Kara Flynn's work on the CLIR Hidden Collections grant. With this milestone in mind, she decided to do a little recap of her work so far.

This month marks the sixth month of my work on the CLIR Hidden Collections grant as the Quaker & Special Collections Project cataloger, and means that my time at Haverford is already halfway over. The past six months have flown by, and I have already learned so much from the materials and the people that I work with here. With this milestone in mind, I decided to do a little recap of my work so far.

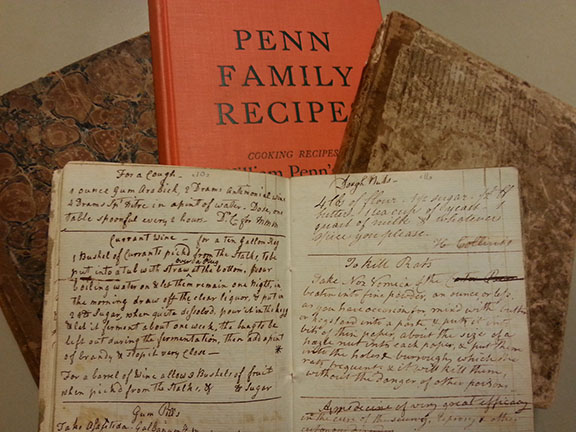

I wanted to start with a recap of the Dig into the Archives event that I planned and hosted on December 11. Entitled, ñA Peck, a Bushel, and a Gill: Recipes from the Quaker Collections,î the event grew out of my interest in three recipe books from the late 18th through mid 19th centuries that I found in the collections I was processing. I thought it would be fun to make a few recipes and have the library staff taste test them for me. After talking about it with a few of the librarians and with Terry Snyder, Librarian of the College, the idea grew into a full-fledged event. We had 12 dishes to taste test, and all of the food was prepared by our wonderful Haverford librarians! We also had a number of recipe books, cook books, and ñcookery cardsî from Quaker & Special Collections on display.

Recipe books are actually quite distinct from our modern cookbooks. Recipe books were compiled by individuals, and were not meant for publication, but rather for personal use. As such, they contained a hodge podge of information related to the individualÍs needs and the needs of their household. For example, you often see not only recipes for food, but also recipes for household goods such as paint or soap, and for remedies and treatments for various illnesses and ailments, as medical care would have largely been taken care of in the home at the time. The earliest recipe book, written by Margaret Hill Morris, had a number of recipes that focused on preserving foods that would quickly spoil, such as meats, cream, and eggs. As technology advances, we see fewer recipes for preserving meat; in the latest recipe book, from 1862, there is no mention of this. MorrisÍ recipe book also reflects the personal nature of these kinds of books. Morris was a widow and mother of four children, and she supported her family by working as a doctor, particularly during the American Revolutionary War. As a result, her recipe book has the most recipes for medical treatments of the three in the collection. Additionally, as medical care becomes more accessible in the 19th century, there are fewer recipes for treatments of illness, though they are still present in the recipe books from the 19th century.

It was also interesting to get feedback from everyone who prepared food on their process. As recipe books were very personal, the recipes are often simply a list of ingredients with proportions. Few recipes have any kind of further direction on the preparation, unlike our cookbooks today. These women would have presumably been taught to cook by the women in their family, and likely copied down recipes from their mothers, grandmothers, or friends. As there was far less variety in food then as there is now, the recipes were likely so familiar that the women who wrote them down didnÍt need anything other than the proportions of ingredients to prepare them. While this was rather inconvenient, it didnÍt faze me too much, because my own mom, who I learned to cook from, is quite inventive with her cooking. She often doesnÍt use a recipe, or only consults one as a suggestion. Since I learned to cook from her, I also donÍt rely too much on recipes. However, when discussing the recipes with my coworkers, I realized that the lack of direction was a real concern for many people who cooked according to recipes, or who didnÍt do a lot of cooking. I found this difference to be intriguing, as I think it says a lot about how the way we think about cooking has changed, and the way we learn to cook, for many people, has changed from something more or less absorbed from an early age from those cooking around you, to something we learn solely from books.

The Dig was a great way to finish up the first half of my time here at Haverford, and as I am halfway through, I thought this would also be a good time to reflect on what I have done so far. In the past six months, I have cataloged a wide variety of materials, including: diaries/journals, correspondence and letterbooks, commonplace books, scrapbooks, signature albums, photo albums, manuscripts/autobiographies/biographies, financial records, and our ñmiscellaneousî materials. Part of why I love working with historic materials is that I am always learning something new, and drawing connections between the past and the present. Working with these materials over the past six months has lead me to think critically about many big, seemingly unwieldy issues, like violence, race, gender issues, and cross-cultural interaction. I think when I tell people (outside of the library) about what IÍm doing, they picture me slogging away in a dim, dusty vault, disconnected from the modern world because I spend all my time reading and writing about historic materials. Not to get too preachy, but nothing could be further from the truth! If I have learned anything in the past six months, it is that people face the same issues across time and space. The iterations of those issues may present themselves differently, but issues of violence, race, gender, and cross-cultural interaction are things we continue to confront today. And this is also why I think it is important to make these collections available to researchers- we now have almost 500 new finding aids online, which, for those of you who donÍt speak library/archive, basically means that if you google using search terms related to these collections, youÍll be able to find them online! And then maybe youÍll be able to use them in your own research, and draw your own connections from them!

If you would like to check out the newly available finding aids online, you can go to the Finding Aids search for the collection number "975."

If you are interested in food, cooking, food history, or want to recreate some historic food in your own kitchen, I suggest looking into the blog, Cooking in the Archives.