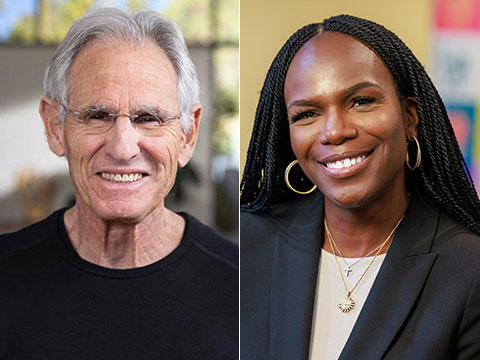

Roads Taken and Not Taken: Lindsay Voigt '03

Lindsay Voigt '03

Details

My first impression of my students was of rows and rows of them marching in formation, covered head to toe in camouflage, their long, shiny black ponytails swinging. They crisscrossed the dirt playing field under the bright blue September sky, the arid mountains of Gansu Province their dramatic backdrop. It was freshman orientation week at Pingliang Medical College, and my students were in military training.

I, too, was a new arrival, fresh off two months of preparation at the Peace Corps China headquarters in the muggy metropolis of Chengdu, where, if nothing else, at least the humidity felt like home. But here in my dry, dusty new home, everything was unfamiliar again. As I piddled around my apartment on my first night, wondering where to begin with cleaning and unpacking, a student knocked at my door. Grinning and bubbly, she invited me to her dorm room, and my walk down the hall with her offered me my first glimpse into the life of a college student in rural China. In one room, students were hand-washing their laundry at huge tile troughs. In the next, I caught sight of a row of squat toilets without so much as a curtain for privacy. We entered her dorm room and before me were four sets of bunk beds and her seven roommates—seven roommates! I realized with horror that in my apartment, composed of two dorm rooms, I was occupying the space of 16 Chinese students. Set into the wall were eight lockers, one for each girl to store all her earthly possessions.

Since that first week of cool observation from afar, when my students marched past in their camouflage, I have come to know them and know something of their stories. The vast majority hail from the countryside, are the sons and daughters of farmers, and are the first in their families to go to college. They have come to Pingliang Medical College, a two-year vocational school, because they did not do well on the paramount college entrance exam and were offered a short list of fields of study from which to choose, one being nursing or basic medicine. They are fully aware that our school is not a good school; they are also aware that it is their only shot at college. Very few are here because they dreamed of a career as a countryside nurse.

Upon acceptance to Pingliang Medical College, students are put into classes of about 50, based on their test scores, meaning that if you know someone's class number, you know exactly what kind of student he or she is. With these 50 classmates, students have all of their classes, which are pre-determined by the school and not chosen by the students themselves. Every night, my students make their way to their“homeroom” classroom, where they have study hall together for two hours, and in the dormitories, the doors are locked and the lights go out at 11:00 sharp. In the morning, they are roused a little after 6:00 and stumble onto the athletic field for morning exercises to the tune of a military march blared through the campus speakers.

Sometimes, as I stroll through the teaching building, I catch a glimpse of my Chinese colleagues teaching. In white lab coats, they stand on platforms wearing lapel microphones, vigorously lecturing rooms of silent students. Knowing that this is what they're used to, and, in fact, what they expect, it's easy to see why students are a little discomfited by my class. I teach Oral English, which by definition requires that students speak, but I learned early on that their speaking is all or nothing. If I pose a simple question to the class like“What does this word mean?” a chorus of 50 voices will knock me backwards, their Mandarin tones emphatically rising and falling together. But an open-ended question like“What do you think about this article?” will cause them to be suddenly fascinated with the books in front of them, leaving me with complete silence and a perfect view of the tops of 50 heads of black hair.

I think about my time at Haverford and of the analysis, research and independent thinking that were the chief end of every class I took, and I realize that none of these even factor into the equation in a place where academic success is determined solely by test scores. My 20-year-old students have never written a research paper and have certainly never been expected to share their own critiques of a situation with their teachers. They often don't know how to take notes or how to study, other than by pacing back and forth around campus, reading aloud to themselves important passages of their textbooks again and again. My fellow volunteers often express frustration at their students' apparent inability to think independently, and we all chuckle at the same canned responses our students spit out in answer to our (we think) deeply probing questions.

Every frustration I've encountered in the classroom, though, is canceled out and then some by the sweetness of being in my students' company. It's impossible for me not to be constantly comparing them to American college students, and harder still to put into words just how innocent they are, and how refreshing this is to me. Most have never been away from home before; many have told me they sometimes cry because they miss their parents so much. Their interests are simple, including taking walks, singing, dancing and playing PingPong. They require very little for amusement: at New Year's, they organized a carnival of trivia games and relay races in the teaching building, with bags of laundry detergent or candy as prizes, and had the time of their lives. Alcohol on campus is a nonissue. They love cheesy pop music and often request me to sing“My Heart Will Go On.” They sometimes hold my hand, often bring me bags of fruit, and always do my soul good.

Sometimes I envy my students the simplicity of their college days. I think about the paralysis of choice that was often the hallmark of my time at Haverford: Summer job or internship? Study abroad? Where? Medieval French literature or Italian poetry? A cappella concert, dance in Founders, or lecture from a visiting professor? It was choices, choices, choices at every turn, and I can't help feeling that the weight of choice, of somehow sealing your destiny with every decision, lies heavy on the American college student. But then I think about my sweet students, these unwilling future nurses of China, and can't help feeling the overriding pain of not having been free to choose in the first place.

Lindsay Voigt '03 is a member of the Peace Corps in China, where she teaches Oral English at a vocational college in Gansu Province.