Haverford College Chemist Part of International Team at NASA

Details

Research currently being conducted at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, may offer new clues about the processes behind global warming trends and their impact on future climate conditions.

Haverford College physical chemist Charles Miller and a team of scientists from around the world are taking the first global measurements of column carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Scientists believe there is a relationship between carbon dioxide and the warming of the Earth's surface.

Their mission, called the Orbiting Carbon Observatory project, is sponsored by NASA's Earth System Science Pathfinder, which funds the development of satellite instruments to make measurements of previously unobserved geophysical quantities. Miller and his colleagues hope their data will enable them to produce an accurate picture of the locations and amounts of carbon dioxide that are being absorbed from the Earth's atmosphere.

Approximately seven billion metric tons of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere every year through human activity. Carbon dioxide's ability to absorb infrared radiation — thereby acting as an insulator of the Earth's surface — makes it a very powerful“greenhouse” gas. While there hasn't been a direct link made between carbon dioxide and global warming, scientists do believe there is a correlation between the two.

“What isn't known is whether CO2 drives temperatures or whether temperatures are responsible for the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere,” explains Miller. "What we do know is that despite the fluctuations in and tremendous amounts of carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere, somewhere the Earth's biogeochemical system is absorbing about half of it.”

Pinpointing the exact locations of carbon dioxide“sinks” or absorption points around the world could have significant political and economic ramifications for countries in those areas. According to Miller, atmospheric scientists are fairly certain that a large carbon dioxide“sink” occurs in the terrestrial Northern Hemisphere, although there's a great deal of contention as to whether it's being absorbed in North America or in parts of northern China and Siberia.“The Kyoto Protocol allows countries to offset their allocated CO2 emissions by the amount of CO2 their land area absorbs,” explains Miller.“If a country can unequivocally demonstrate that it's doing things to absorb carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, it could mean significant political and monetary credit for that country,” he says.

Still, scientists are uncertain as to whether carbon dioxide is being absorbed by the soil or, as in the case of Brazil, by large forested areas.“We do know that the rainforest area absorbs huge quantities of CO2,” says Miller,” but we don't know if the rain forest is a net sink since decaying vegetation and leaves can release large amounts of CO2. It is unclear how much decayed organic carbon is sequestered in the soil and how much is transferred into the atmosphere. ”

Miller points out that the larger question is in why the accumulations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere fluctuate from year to year.“We must understand the processes better so that we can better predict how the Earth's systems will respond to future changes in climate.”

The OCO satellite is scheduled to launch in August 2007. Over the next 24 months it will orbit the Earth from pole to pole 14 times per day, recording data on the sunlit side of each orbit. Every 16 days the Earth's rotation will return the orbit to its“starting point” and thus provide a global map.

Miller, who is the project's deputy principal investigator, is working alongside a number of atmospheric scientists from Caltech, the University of California, Berkeley, Harvard, the University of California, Irvine, Colorado State University, the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and scientists representing environmental agencies from Australia, France, Germany, and New Zealand.

An assistant professor of physical chemistry, Miller and his Haverford research students began laying the groundwork for this project three years ago when they started fundamental research on carbon dioxide molecules using infrared spectroscopy. In the course of their research, which frequently takes them to the Kitt Peak National Solar Observatory, they discovered new absorption features of some of the rarer isotopimers of CO2. They also were able to confirm the accuracies involved in measuring the frequencies and energy absorption strengths of CO2.“This information was very important for ensuring that we had the most precise measurements possible once we started retrieving CO2 for the Orbiting Carbon project,” says Miller.“The same information can also be used to measure the CO2 column over a single ground location by having a ground based spectrometer stare at the sun.”

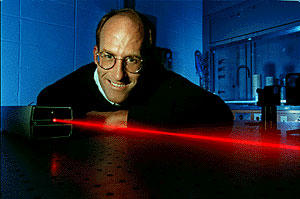

A specialist in atmospheric chemistry, Miller joined Haverford College's chemistry faculty after three years with the Atmospheric Kinetics and Photochemistry Group at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. There he studied the photochemistry, reaction rates and kinetics of atmospheric molecules, designing a laser system to observe the kinetics of HO2. Prior to that he was a post-doctoral research fellow for Nobel Laureate Robert Curl at Rice University's Rice Quantum Institute.

Miller's research, which has implications for studying ozone concentrations and long-term atmospheric trends, has been published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry, the Journal of Chemical Education and Science. His current project is being supported by a three-year, $300,000 grant from NASA's Office of Earth Sciences.

In early September Miller participated in a special session on the chemistry climate change at the American Chemical Society meeting in New York.