Ghost of Shakespeare Thrives at Haverford: Students and Faculty Proclaim Report Of the Bard's Death on Campus Is an Exaggeration

Details

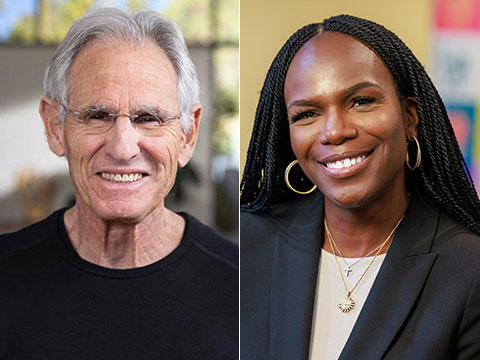

This fall, nearly three times the allotted class enrollment signed up to take Kim Benston's course, "Shakespeare: The Tragic and Beyond." The demand was so high, Benston cancelled a course he planned to teach this spring so he could offer yet another Shakespeare class to accommodate the overflow.

For anyone who read press accounts of the demise of Shakespeare on college campuses last winter, the playwright's popularity at Haverford may seem as confounding as when his not yet dead but very neurotic Hamlet proclaims "I am dead" in the final scene of the play.

In the press stories, several scholars argued Shakespeare was indeed a dead subject on college campuses since many prestigious colleges - including Haverford - did not require English majors to take a Shakespeare course. The articles were based on a survey by the National Alumni Forum which reported dwindling numbers of colleges and universities that required Shakespeare for their English majors. The report concluded this phenomenon was indicative not only of a lack of interest in William Shakespeare, but a belief on college campuses that Shakespeare was no longer relevant to the study of literature.

"Most English departments are now held so completely hostage to fashionable political and theoretical agendas that it is unlikely Shakespeare can qualify as an appropriate author," said an alarmed Robert Brustein, artistic director of the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

But at Haverford, which has never required its students to take a course on Shakespeare, Benston said The Bard seems to have an allure with students of all majors.

"It's very interesting that in this moment when people claim that Shakespeare is dead, there seems to be a huge demand for Shakespeare in the popular culture," Benston said. "Just look at the number of films that have been made. Shakespeare is quite a consumable good right now. It's ironic that at the very time he is being considered an obliterated white male, the spirit of his ghost is looming quite freely on college campuses."

Benston said there are currently three new editions of Shakespeare's works compiled by scholars whose literary political agendas run the gamut from conservative to radical.

"Shakespeare actually lived in a period where the same issues were on the table," Benston said. "England was exposed to a sudden influx of alien cultural images and diverse new influences, and there were the same arguments between preserving a distinctly English culture and admitting challenging alternatives."

But for Haverford students, this ongoing debate about curriculum may seem to be much ado about nothing. They just like reading Shakespeare, and the number of students interested in taking a course on his work overshadows any accounts of his demise in English departments.

"There are so many interesting passages and ways to look at the language and imagery," said sophomore Claire Gallagher, one of 30 students who won a registrar's lottery and a seat in Benston's class this fall. Gallagher said Shakespeare seems so relevant to many of the issues in the world around her - including the death penalty.

Gallagher explained she had just attended a lecture with Sister Helen Prejean who spoke out against the death penalty. Gallagher explained how Prejean described the families of murder victims and their varying attitudes toward the perpetrators and their appropriate punishments.

"The whole idea of whether or not to take revenge is a big issue in Hamlet," Gallagher said. "His father's ghost basically tells him, 'leave your mother to God,' but to take revenge on Claudius for the death of the king. These people are basically dealing with the same issues when it comes to the death penalty."

Although Benston said he can't presume to understand the surge in student interest, he noted that college students encounter Shakespeare more in the popular culture than they did 20 years ago. With so many Hollywood film versions, Benston thinks Shakespeare may be seen less as a "high culture" author and thus more approachable both to majors and non-majors. He noted the demand for the course was about equal between English majors and other majors.

"It's notable that students seek the class in the absence of a specific requirement," Benston added. "They didn't come here driven by some dictate that they had to read Shakespeare."

As for what students take away from the class, Benston said he hopes it is an understanding of complexity not only in Shakespeare's language, but in our modern society.

"Our students are trying to find themselves in a culture that's in tremendous flux," Benston said. "I hope they discover that their lives are a lot more intricate than they ever imagined, and that there are many possibilities for creative response to complex experiences."