COVID-19 takes aim at Chicago's Latino community, many without health care

In the state of Illinois, Latinos make up nearly half of all positive cases.

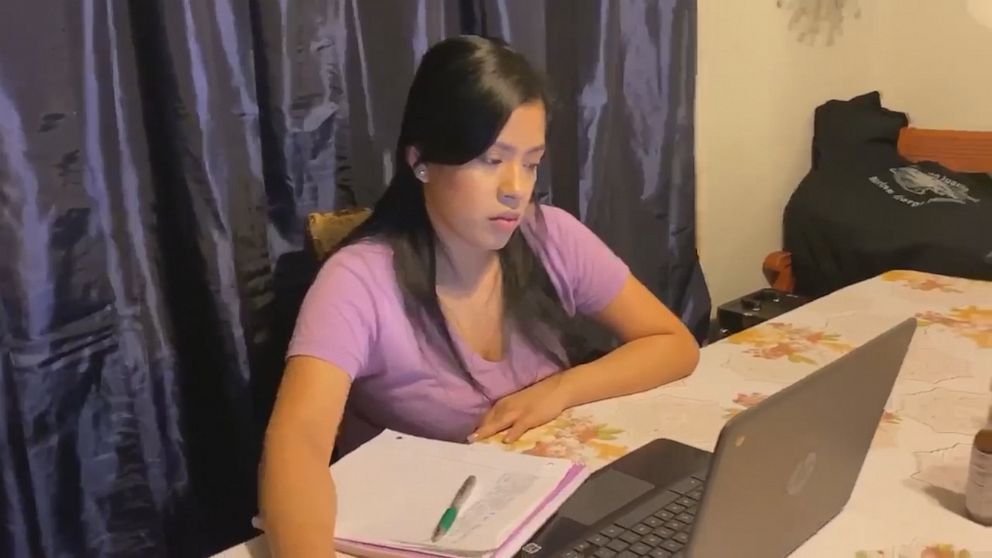

On the south side of Chicago, Estefania Ramirez is still somewhat in disbelief two weeks after testing positive for COVID-19.

“I still don't think that it’s real,” she told “Nightline.” “When it started, I thought that I was going to get it if I went out to the stores, my job, but I never expected that I would get it inside my house.”

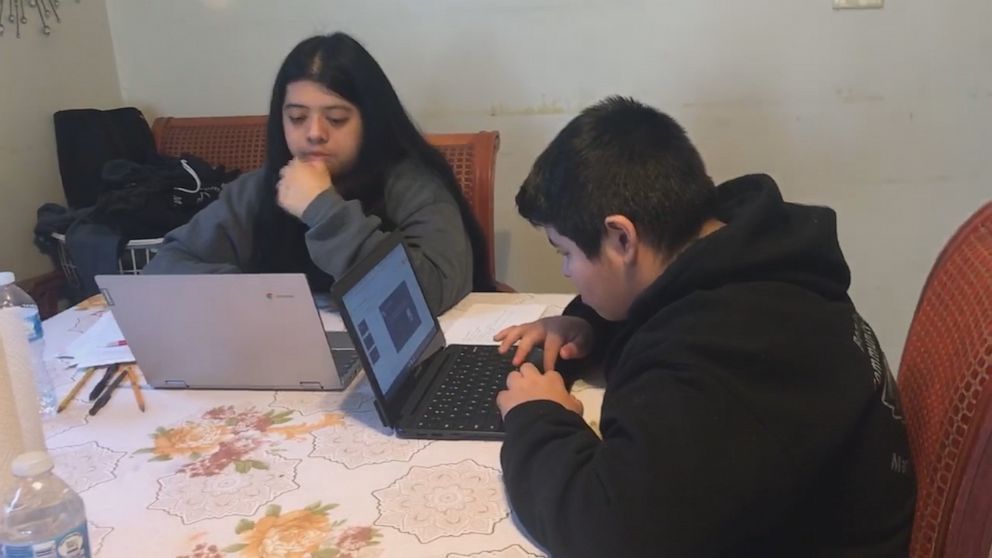

Ramirez contracted the coronavirus inside the apartment she shares with her parents and two younger siblings. It’s a home full of essential workers: Ramirez works at an Amazon warehouse and her father works at a meatpacking factory.

“I felt kind of helpless … because I knew that if one of us got it, we were all going to be exposed, no matter what we did,” Ramirez said.

Watch the full story on "Nightline" TONIGHT at 12:05 a.m. ET on ABC

Ramirez believes it was her father who was first exposed to the virus and that he brought it home.

“A lot of people got infected and he came in contact with one of those people,” she said. “A few days later, he started with the symptoms and then my mom and then eventually me.”

Ramirez's mother, Maria Ochoa, first started having back pain, then came body aches and a fever.

“I felt that inside. My brain felt super big and it felt really hot, like smoke was coming out of my head… It felt like I was in an oven,” Ochoa said in Spanish.

In the middle of the night, Ramirez rushed her mother to the hospital.

“Thinking that my mom was gonna stay in the hospital and that she could die, that was my biggest fear,” Ramirez said.

The Ramirez family, like so many of their neighbors, knows going to work and risking exposure to COVID-19 is one they have to take in order to put food on their table.

Chicago is a city that came back from the ashes more than a century ago, and it's now finding its footing amid another tragedy. First, COVID-19 ravaged its African American community. Now, the fast-moving killer is taking hold of yet another group: Latinos.

“I think it has to do with the fact that Latinos are a big part of the backbone of the economy,” emergency physician Marina Del Rios told “Nightline.”

Almost half (41%) of the state's total infections have been Latino, though Latinos represent only 17% of the population. The majority of the positive cases can be narrowed down to five zip codes in Cook County, outlining what’s known as the heart of the Latino immigrant community in the Midwest.

In these black and brown neighborhoods, working from home isn’t an option for many residents, some of whom are undocumented immigrants. Their community is chronically underserved and often ignored.

The death toll in this county of more than 3,000 people is painful, but no surprise to those who live here.

Across the country, black Americans and Latinos are nearly three times more likely to personally know someone who has died from COVID-19.

That statistic lays bare the divide these communities feel between themselves and those with privilege.

“This thing is taking out entire families,” Del Rios told “Nightline.” “It's also the fact that when you're poor, you can't eat very well. When you're poor, you may not have access to medications to make you feel better. Physical distancing is a privilege and keeping yourself healthy is a privilege.”

For the Ramirez family, the moment they started feeling symptoms, there was nothing they could do.

“I heard that you had to isolate from everybody, like stay in one room. Obviously, you wash everything that you touch,” Estefania Ramirez said. “I knew that it was not going to be possible for us because we use everything.”

To them it was clear: They had all fallen victim to the virus.

But they say the economic side effects is what worried them more.

“I do not feel very secure because I do not have health insurance,” Maria Ochoa said.

The Ramirezes are a mixed immigration status family; some are U.S. citizens while others are in the process of seeking residency. Estefania is a DACA recipient, which means that while she cannot seek residency, she is allowed to live and work in the U.S. The three hardest hit by COVID-19 are the breadwinners. Yet, because of their status, none of them are eligible for federal stimulus relief and all of them are out of work. A medical bill would mean sacrificing their savings.

“I think what makes a difference is, for instance, my parents, especially my dad, if he wants to get medical attention, they have to think twice of how are they gonna be able to afford it,” Ramirez said. “They kind of think twice about going to an emergency room or going to get checked by a doctor.”

Many Latinos are waiting until their symptoms become severe to get tested.

“When it came back positive, I was like, ‘Oh, it's real.’ And like I said, [I was] a little bit scared because I still had the symptoms and I didn't know if … I was gonna get better or worse,” Ramirez said.

Frustrated by the lack of resources, community activists are taking matters into their own hands.

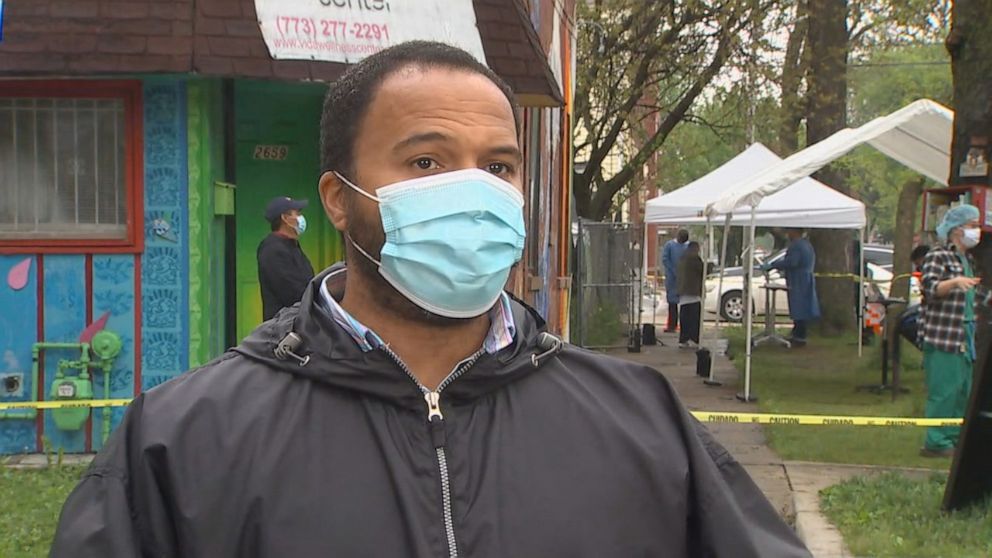

Jerome Montgomery runs Project Vida, a fixture in the Little Village community for 28 years.

Project Vida's focus is usually on HIV and AIDS, but seven weeks ago it pivoted to COVID-19 to bring much needed testing to this community.

“We wanted to bring more services into the community because we knew this pandemic was impacting the Latino and African American communities,” Montgomery said.

Project Vida joined forces with another community leader, Howard Brown Health.

“One of the things that I'm very proud of is that we're able to see an individual, regardless of their documentation status, regardless of their ability to speak English or regardless of their ability to pay,” Mario Treto Jr., board chair of the center, told “Nightline.”

That’s one of the reasons why the clinic is intentionally tucked away in a quiet corner of town.

“It definitely helps to remove some of the stigma,” Montgomery said. “It also helps to remove some of the fear, because you have that trusted name that you're coming to.”

Drew Guzman is one of the doctors there.

“One thing that was really, really salient to me was seeing a lot of families coming in who were getting tested after having a relative pass away,” Guzman said. “That's something that has kind of really stuck with me.”

More than 50% of the clinic’s patients have test positive for the coronavirus, while more than 80% have come in without insurance.

“I don't think people understand the true public health issue that it is,” Montgomery said. “If we're unable to provide services or care to a particular individual or populations that are vulnerable, it will, too, get to those rural areas or those less, less populated areas.”

After every positive result, a team conducts contact tracing, tracking down all those who may have come close to the infected person.

“When we're talking about ‘flatten the curve,’ we have to make sure that we're actually out there doing the testing, doing contact tracing, doing the other things that are necessary to make sure we gain an understanding of just how deep the pandemic is,” Montgomery said.

As long as the lines keep forming, Montgomery and his colleagues will keep working. Montgomery said he's been working from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.

“You know, the obvious need within the community and the lack of response is very frustrating. But at the same time, we have some amazing people out here on the frontlines -- the doctors and nurses. Those give you some hope. But we still have a long way to go.”

Dr. Marina Del Rios works in the emergency department at the University of Illinois Hospital.

“What I'm seeing is that in the minority neighborhoods, especially the number of positive cases, is twice and sometimes even three times the number of positive cases that we're seeing in white, more affluent neighborhoods.”

A proud Puerto Rican, Del Rios stands out in the field of medicine, where less than 6% of all doctors are Latino.

“It's unnerving to see that I'm seeing more and more people walking in that look like my [uncles] and [aunts], or that could, you know, that remind me of my mom,” she said.

Del Rios is part of the Illinois Latino COVID-19 initiative which launched last month in response to the crisis.

“We're here not because of COVID, but because of decades of structural racism that had kind of built up to this."

She pointed to research that people of color are more likely to be triaged as less urgent for similar illnesses as a white person.

“We know that patients that are in pain, that are black and brown, are often not treated with the same amount of pain medication as the people who are white,” she added. “When you compound that with the language barrier that Latinos have, and that problem even becomes amplified further.”

Del Rios agrees with the idea that any community left in the lurch is an enormous public health risk to all.

“You're only as healthy as your most vulnerable members of the society,” she said.

Erendira Rendon is an immigration advocate for the Chicago-based nonprofit The Resurrection Project. She says the fear of COVID-19 is one that accompanies the fear of sliding further into poverty for many families.

“I think right now these two fears are so overwhelming to our families that it's becoming, you know, another pandemic that the Latino families ... are facing,” Rendon told “Nightline.”

It all weighs heavily on Rendon; both her parents are undocumented and most of her family has tested positive for the virus. She says that while the virus has attacked more than half a million undocumented immigrants in the state of Illinois, relief has been absent.

“There are no benefits, there's no unemployment, there's no stimulus check that's going to come to the folks that we work with,” Rendon said. “They're left with no option but to go to work or to find a way to be able to make a living.”

In an effort to lend a helping hand, The Resurrection Project created a donation-based fund, which hand-delivered a check to a family desperately in need last Friday. With four children in the family, their father hasn't worked since the beginning of March as the coronavirus caused shutdowns.

“Hopefully that helps as they get on their path to recovery,” Rendon said.

“From a public health perspective, we need to be able to assure that people that need to quarantine can stay home. And that means that they need to be able to still pay their mortgage, need to be able to still pay their rent, pay their bills ... put food on the table,” she said. “That means that we have to give people money to be able to do that.”

After two weeks, Estefania Ramirez and her family are recovered from the coronavirus. But now that they are going back to work, they know they’re putting themselves at risk again.

“What I need to have to feel back to normal, I think, is having a cure for the disease," Ramirez said, "and also ... having a vaccine for it to feel safe that I won't get infected again, or my family."

This report is part of "Pandemic – A Nation Divided," ABC News' special coverage of the heightened racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Tune into "Nightline" for the last of a three-day series this week, 12:05 a.m. ET on ABC.